Why You Can’t Trust Your Gut: The Hidden Timeline of Food Poisoning

Why You Probably Won’t Know What Gave You Food Poisoning

You eat a salad for lunch. Six hours later, you’re doubled over with stomach cramps, nausea, and diarrhea. It must’ve been the romaine—right?

Not so fast.

According to Dr. Denise Monack, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford Medicine, most common foodborne pathogens don’t strike right away. In fact, they can silently multiply in your gut for hours or even days before symptoms appear.

That means the culprit might not be your lunch—but last night’s dinner, yesterday’s snack, or even something you ate three days ago.

The Usual Suspects: Common Foodborne Pathogens

In the U.S., the top causes of food poisoning include:

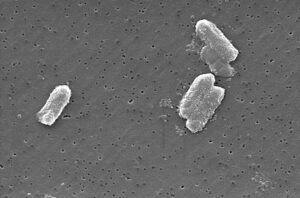

- Salmonella

- E. coli

- Campylobacter

- Norovirus

Unlike toxins from spoiled fish or certain mushrooms—which can cause vomiting within minutes—these microbes need time to colonize your intestines and reach numbers high enough to trigger illness.

“It’s not an instant reaction,” says Dr. Monack. “The pathogen has to grow, adapt, and outcompete your normal gut bacteria before it makes you sick.”

This delay creates a diagnostic blind spot—especially since people who ate the same contaminated food may fall ill at different times… or not at all.

Why Do Some People Get Sick and Others Don’t?

Not everyone exposed to a foodborne pathogen becomes ill. Your risk depends on several factors:

- How much of the pathogen you ingested

- Your gut microbiome composition

- Your immune system strength

- What else you ate (certain foods can feed or inhibit pathogens)

For example, fiber-rich foods may actually help some bacteria like Salmonella thrive, as they break down dietary fibers to release sugars they can use for energy—a process Dr. Monack’s lab recently uncovered.

This variability makes it even harder to trace an outbreak back to a single source.

How Long Does Food Poisoning Last?

Most healthy adults recover within 2 to 5 days. But some pathogens can linger in the gut for up to a week or more.

Dr. Monack advises:

- Drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration

- Avoid high-fiber foods temporarily (they can fuel pathogen growth)

- Use acetaminophen for fever—but skip antibiotics unless absolutely necessary

“Antibiotics kill off good gut bacteria that help you recover,” she warns. “There’s no magic bullet that targets only Salmonella or E. coli—so we usually let the immune system do its job.”

If symptoms last longer than 10 days, seek medical care.

Where Do These Pathogens Come From?

In the U.S., contamination usually happens through:

- Undercooked meat or poultry

- Raw seafood

- Fresh produce exposed to animal feces (via soil, water, or fertilizer)

- Norovirus spread by infected people touching surfaces or food

Unlike in many low-resource countries—where poor sanitation leads to widespread waterborne illness—food poisoning in the U.S. is typically sporadic and short-lived.

Still, it’s preventable.

Smart Steps to Reduce Your Risk

You don’t need to live in fear of your kitchen. Just follow these evidence-based practices:

✅ Wash hands thoroughly before cooking and after handling raw meat

✅ Clean countertops, cutting boards, and utensils after contact with raw foods

✅ Cook meats to safe internal temperatures (use a food thermometer)

✅ Refrigerate leftovers within 2 hours (1 hour if it’s hot outside)

✅ Avoid leaving perishables like potato salad out at picnics—bacteria multiply fast at room temperature

Even Dr. Monack, who studies Salmonella daily, admits:

“I skip the picnic potato salad—but I still enjoy my burgers slightly pink. You can be cautious without being paranoid.”

The Global Picture: Food Safety Isn’t Equal

While food poisoning in the U.S. is usually a temporary inconvenience, it’s a leading cause of death in children in developing regions—where contaminated water and inadequate sanitation allow pathogens to spread widely.

Repeated diarrheal illnesses can lead to malnutrition and stunted growth, highlighting why global food and water safety remains a critical public health priority.

Final Thought: Trust Science, Not Guesswork

Your gut may be unhappy—but it won’t tell you why. Because of the delayed onset of symptoms, blaming the last meal you ate is almost always wrong.

Instead of guessing, focus on prevention and supportive care. And remember: your immune system—and your gut’s good bacteria—are your best allies in fighting off foodborne invaders.

Stay Informed on Microbiology & Public Health

At ClinicalMicrobiology.org, we break down complex infectious disease topics into actionable insights for clinicians, researchers, and health-conscious readers.

👉 Subscribe today for expert updates on pathogens, prevention, and the science behind everyday health risks.

Note: This article is inspired by reporting from Stanford Medicine (March 9, 2023). Scientific insights credited to Dr. Denise Monack. All content has been fully rewritten for originality, clarity, and educational value.

Post Comment